Over the Influence

An appeal for snobbery.

This is Why We Have to Go Back to Beating Up Nerds

It’s no exaggeration to say that American culture, such as it was, was bludgeoned to death screaming on May 31st, 2014, the day Anna Wintour put Kim Kardashian on the cover of Vogue.

Okay fine, that’s an exaggeration. But not by much.

Just consider the diverging fortunes of each in the ensuing decade: Vogue sank into a clearinghouse for e-comm and second-rate nepo babies, whereas Kim Kardashian somehow transformed from the talentless patron saint of slack-jawed mall sluts into the Millennial’s Babe Paley. It’s not hard to see which picked up the shine and which the smudge.

Anna Wintour’s main job, the singular duty that came with all the money and perks and cachet of leading that magazine, was to defend the commercial value of snobbery at all costs—to hold fast against the vulgarians at the gate. A reality show, no matter how expensively produced, is still a cheap thing, and cheap things are not supposed to be on the cover of Vogue. But in the face of a vacuous star-fucking nobody—albeit an overwhelmingly vacuous star-fucking nobody—the queen of taste bent the knee to the forces of banality.

After Kim, the deluge.

In lowering the drawbridge to the reality show horde, Wintour also helped sanctify the gibbering insta-pundits, waxed loudmouth gym bros, athleisured Silicon Valley charm vacuums, and the eventual swarm of micro-influencers who now overrun the Paris and Milan shows, Pebble Beach, Dubai Watch Week, and anywhere else with a DJ booth and an open bar. In effect, she forced the various high priests of culture both inside and outside her magazine—designers, photographers, critics, artists and the rest—to watch their own ransacking, their accumulated capital carted out the door and redistributed as a wide, thin sheen of egalitarian expertise.

It’s worth remembering that not so long ago we considered intellectual property to be the purview of the creator, and defended it at the business end of a gun: reproducing a copyrighted film or rebroadcasting a football game might get you a door-kick from the FBI and up to five years in prison. Now you can build a legitimate and entirely lucrative content career using nothing but creatively repurposed sports highlights or movie clips or old runway shows.

A lot of influencer content is, it must be said, fantastic; some of it surely rises to the level of art. But it’s a different job than what a Vogue editor does, or it should be different, or at least it used to be. The crucible of working for the legacy media, especially early in your career, is that you have to earn your opinion. Between editors, creative directors, fact-checkers, photo researchers, and staff writers all trying to knock the legs out from under every pitch as part of the job, the process for getting an idea onto the printed page is the creative equivalent of being beaten into a gang every month. In return, you’re given privileged access by which, over time, you can form qualified opinions. If you write about clothes, you can visit the factories where textiles are produced, or have a designer personally walk you through her latest collection; if you write about watches, you can witness the alchemy of grand feu enameling and then talk to a master engraver about tremblage while he’s still in his smock and binoculars. Before any of this was understood as content, it was simply considered research, part of the job—a quiet study of beauty and philosophy and rigor made available by the institution to its initiates, like the Jesuits or the Buddhists do but with frivolous dinners and gift bags and afterparty cocaine.

The influence economy, on the other hand, is fundamentally populist. The influencer’s excitement is purchased directly, no different than the Roman operae paid to spread sentiment throughout the Forum, with access and perks only granted after sufficient loyalty has been demonstrated. That’s not worse than the institutionalist approach, just different—or it should be. In a healthier consumer ecosystem, editor and influencer could coexist separately, side by side, but over the past decade something unnatural and very disgusting happened and now you can’t necessarily tell them apart. There are too many of them, and they’re all constantly jostling and bleating for the same resource: money by way of attention, otherwise known as the Kardashian Sex Tape Principle.

Most of the money and much of the attention is going to noted influencer Elon Musk and others who own social media algorithms like his, the ones who control the attention pipes that fuel the creator economy. And also those who own AI concerns such as his, which promise to keep the economy but replace the creators. There’s a certain depressing poetry to that logic; it's the concise expression of a thoroughly tacky worldview.

The trillion-dollar distillation of the attention economy is a pale, tasteless dork in a cowboy hat awkwardly dancing with robots at his own backyard wrestling show. We should have been laughing at it the whole time.

And now, shirts!

Ram Blue Is the Warmest Color

As far as lovely clothes go, I’m set for life by any definition short of the obnoxious; on the other hand, I didn’t have a spread-collar oxford cloth shirt in Ram Blue with slightly chunky mother-of-pearl buttons—and, really, what would the neighbors think?

I spotted the Ballard Mother of Pearl Oxford at Alfargos Marketplace during its first outing at the Moxy, in Williamsburg; I was walking around with a designer for Ralph Lauren and we both wound up at the Ballard display from different directions—it’s quite a unique blue in person, rich and slightly warm, and it draws your eye in a crowd.

A few weeks later, Ballard founder Harry Moore met me for an afternoon coffee in the West Village so we could exchange my medium for a large. He has an interesting background, studying product design before going to work for casualwear behemoth Peter Millar in his home state of North Carolina—which, when he mentioned it, immediately explained the particular shade of blue—then whiplashing over to New York City and one of the hippest, vibe-iest crews in menswear, Aimé Leon Dore, with a stint at Ralph thrown in for good measure.

The shirt shows its influences. The fit is relaxed but without an iota of bulk, a trick that can only be pulled off with a product designer’s eye for precision. The soft hand of the mid-weight Japanese oxford cloth drapes somewhere between a dress shirt and your oldest Brooks Brothers, but the buttonless collar, with its generous spread and elongated points, adds a relaxed horse-country vibe, almost like a Western shirt. It’s somehow like the essence of every OCBD you’ve ever owned while remaining fundamentally different from all of them.

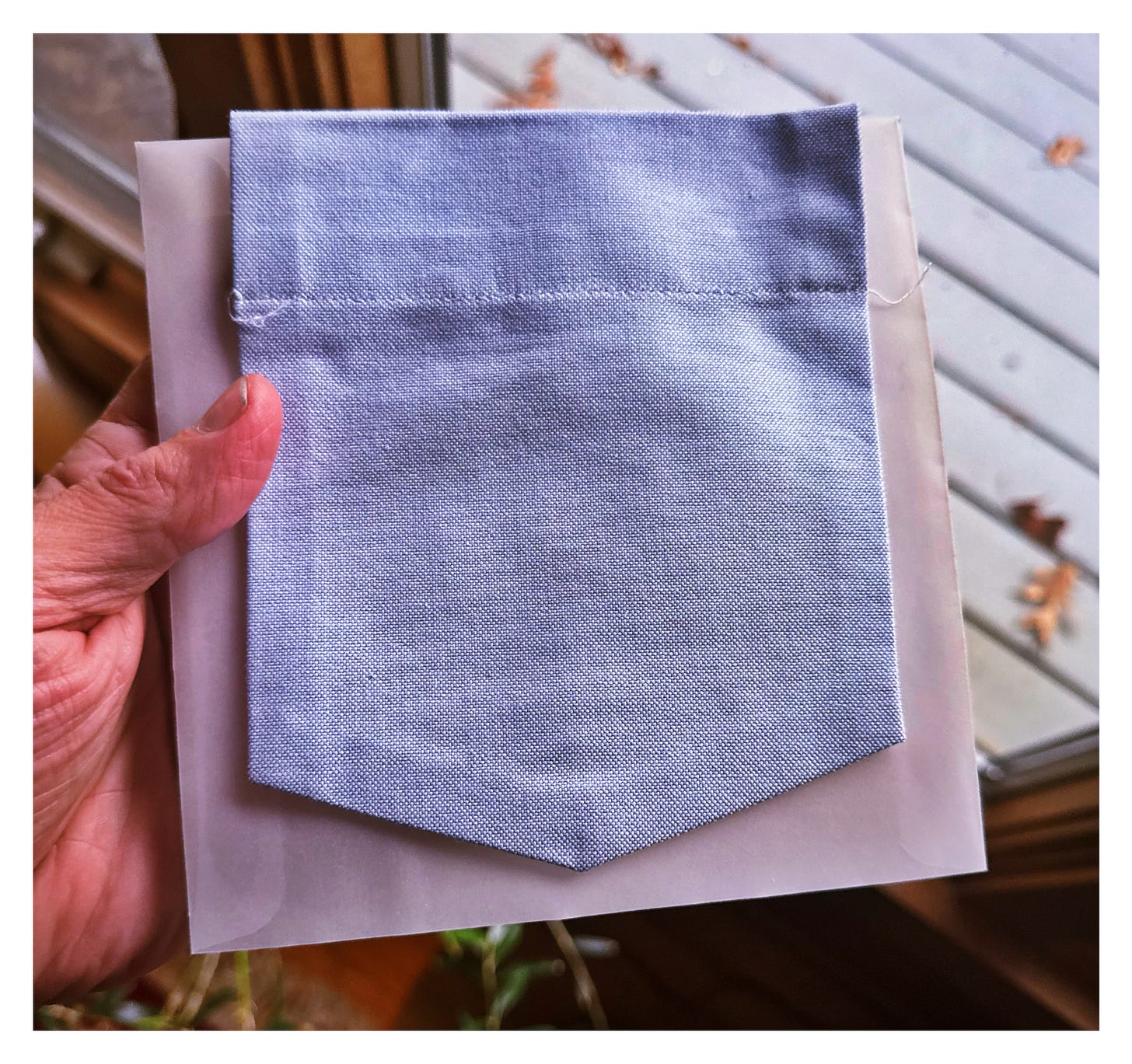

My favorite part is that if you order the shirt with a pocket, the pocket arrives detached so your tailor can position it exactly where you prefer. It’s one of the many small details that explains the $175 price point, which can be considered a lot to pay for an oxford-cloth shirt but very little for a luxury good constructed with this level of obsession, sourcing, and attention to detail.

So I have that going for me, which is nice.

-J

I'm a card-carrying snob! I think the thing about Wintour and her promotion of people like Kim K is that it's (shamefully) fully in alignment with her taste – because it's awful. As Azzedine Alaïa said in one of my favorite interviews of all time, "When I see how she is dressed, I don't believe her tastes one second." But I think taste is a big issue that needs to be addressed across the board. It certainly seems to have been completely sucked out of just about all mainstream publications at this point. I grew up loving magazines so much, and I hate that I don't feel that way about them anymore.